Off (Jefferson’s Grid)

2018-PresentPublished: Countryside, A Report

CANActions Magazine ЗЕМЛЯ | THE LAND

Lecture:

08.20.20 CANActions Live

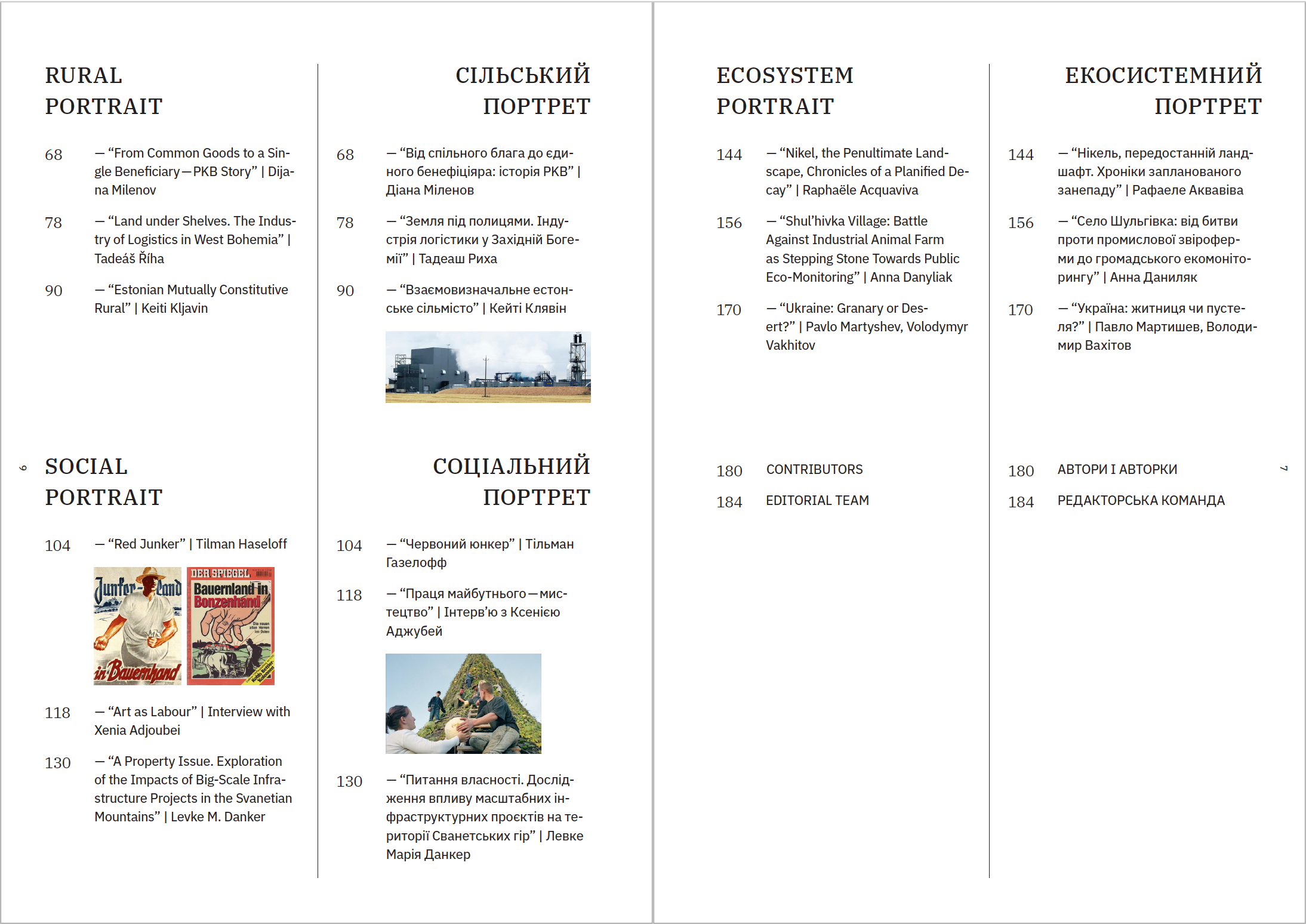

‘The grid’ is

America’s creation myth: a Cartesian

projection that parceled the vast expanses of the western territories, sight

unseen, into 6-square-mile townships, 640-acre parcels, and 160-acre lots1.

A speculative armature, the Land Ordinance of 1785 (Jefferson’s Grid) was a

tool of expansion, commerce, and control.

Its unstoppable westward trajectory was not only righteous but preordained—Manifest

Destiny.

The unfeeling

surveyor’s line prefigured blankness: a single stroke on paper transformed

wilderness into civilization, amputated rivers and mountain ranges, and

decimated indigenous populations—a tool of erasure as well as creation. Today, Jefferson’s

Ggrid covers 75% of

the continental United States: a flexible matrix better suited to developers,

big banks, and big business than to the now defunct dream of an agrarian

democracy.

[1]When discussing the Jeffersonian Grid and the Homestead Act this essay uses imperial units (acres and miles) because they have assumed a numerological significance in the American psyche that approaches the occult symbolism of seven or forty in the Bible.

[1]When discussing the Jeffersonian Grid and the Homestead Act this essay uses imperial units (acres and miles) because they have assumed a numerological significance in the American psyche that approaches the occult symbolism of seven or forty in the Bible.

Threaded through the extra-large organizational framework of the nation—the survey grid that divided the west before we’d even seen it—are places and people that, to this day, resist cultivation, organization, and the grid’s imperative of productivity.

The South West, the most inhospitable swathe of desert, is where the grid’s true nature is revealed. It is America’s back of house, where things that are too big, too ugly and too distasteful happen. Land that the US government was giving away to homesteaders as recently as the 1970s is now an industrialized infrastructure of solar farms, feedlots, monoculture, irrigation canals, and highways. Manifest Destiny’s end of the line. Everything is on its way somewhere else, an unstoppable flow of commerce that moves in the L-shaped path of a knight on a chessboard: water, energy, crops, and long haul truckers sliding along the X and Y axes of America’s grid.

IMPERIAL COUNTY

The 10 freeway stretches from the Pacific to the Atlantic, but the glints on the horizon are only shining seas of solar farms. The roadside is punctuated with increasingly dire warning signs: they caution not to pick up hitchhikers near Ironwood State Prison; to be aware of poisonous snakes and insects; and declare Brush Fire Level HIGH. The map is populated with names like Mirage, Siberia, and Bagdad, a nod to both extreme remoteness and extreme climate. The heat is alien, almost sentient in its hostility—it’s 9:00am and well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit (37 Celsius). Imperial County is a complex ecosystem; a swirling Cartesian vortex of big-box retail, feedlots, solar farms, ICE Border Control checkpoints, drainage ditches, and train tracks. Rows of date palms emerge on the edges of Coachella and Palm Springs: twinkles of escapist leisure and flower crowns on the periphery of a landscape the US Military thought was perfectly suited to mimic the conditions of desert warfare.

Out of the Sonoran Desert, in the sunniest place in the United States, miraculously, there are bleached green fields unrolling as far as the eye can see [Fig. 2,3,4]. The Imperial Valley, the largest alfalfa-growing region in the world, is irrigated by an improbable muddy trickle of the hyper-controlled, over-allocated Colorado River, cutting through the desert via1,600 miles (2,574 km) of the All-American Canal [Fig. 6]. Throttled by thousands of kilometers of concrete channels, levees, and dams, the Colorado River is amputated at the Mexican border. While goods and capital are free to flow—people and water are brutally stymied. The Imperial Irrigation District, just north of the border, consumes 20% of the Colorado’s rapidly diminishing supply, three-quarters of California’s total allotment (the most populous state in America), and twice as much as the entire country of Mexico.[1] [2]

1. The Colorado River Compact is an agreement between seven states: Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, and California intended to fairly distribute the available water. The river rarely reaches its natural termination point in the Gulf of California, decimating a once-thriving ecosystem.

2.Joassart, Pascale, Fernando Javier Bosco, Alida Cantor, Jody Emel, and Harvey Neo. “Networks of Global Production and Resistance: Meat, Dairy, and Place.” Essay. In Food and Place a Critical Exploration, 41–42. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018.

Between one-third and one-half of alfalfa grown in

the Imperial Valley, irrigated by the dwindling river, is exported abroad to Japan,

Taiwan, South Korea, China, Saudia Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and

Mexico.[1]

[2] The Saudi Arabian company Almarai and

its subsidiaries own close to 12,000 acres (4,856 hectares) in California and

Arizona and Al Dahra ACX, the number one exporter of forage in the US, is a

United Arab Emirates company with farms in the Imperial Valley.[3]

[1] The Orwellian absurdity of global supply chain logistics, trade patterns, and shipping networks means it’s cheaper to ship the alfalfa to China, than California dairy farms. [2] China, the UAE, and many of the other countries that import alfalfa from the American South West either explicitly forbid, or don’t allocate land, for the growing of forage (animal feed).

[3] IBID 41–42

[1] The Orwellian absurdity of global supply chain logistics, trade patterns, and shipping networks means it’s cheaper to ship the alfalfa to China, than California dairy farms. [2] China, the UAE, and many of the other countries that import alfalfa from the American South West either explicitly forbid, or don’t allocate land, for the growing of forage (animal feed).

[3] IBID 41–42

The physical and political infrastructure of the

Imperial Valley, the grid, is a scaffolding for an alchemical transformation:

water is transformed into animal feed, animal feed into milk, and milk into

money. Emptied out and optimized, any feature of the land that does not

contribute to increased yields or profit has been erased—inured to social and

ecological consequences the grid persists, a smooth conduit of global supply

and demand.

THE SALTON SEA:

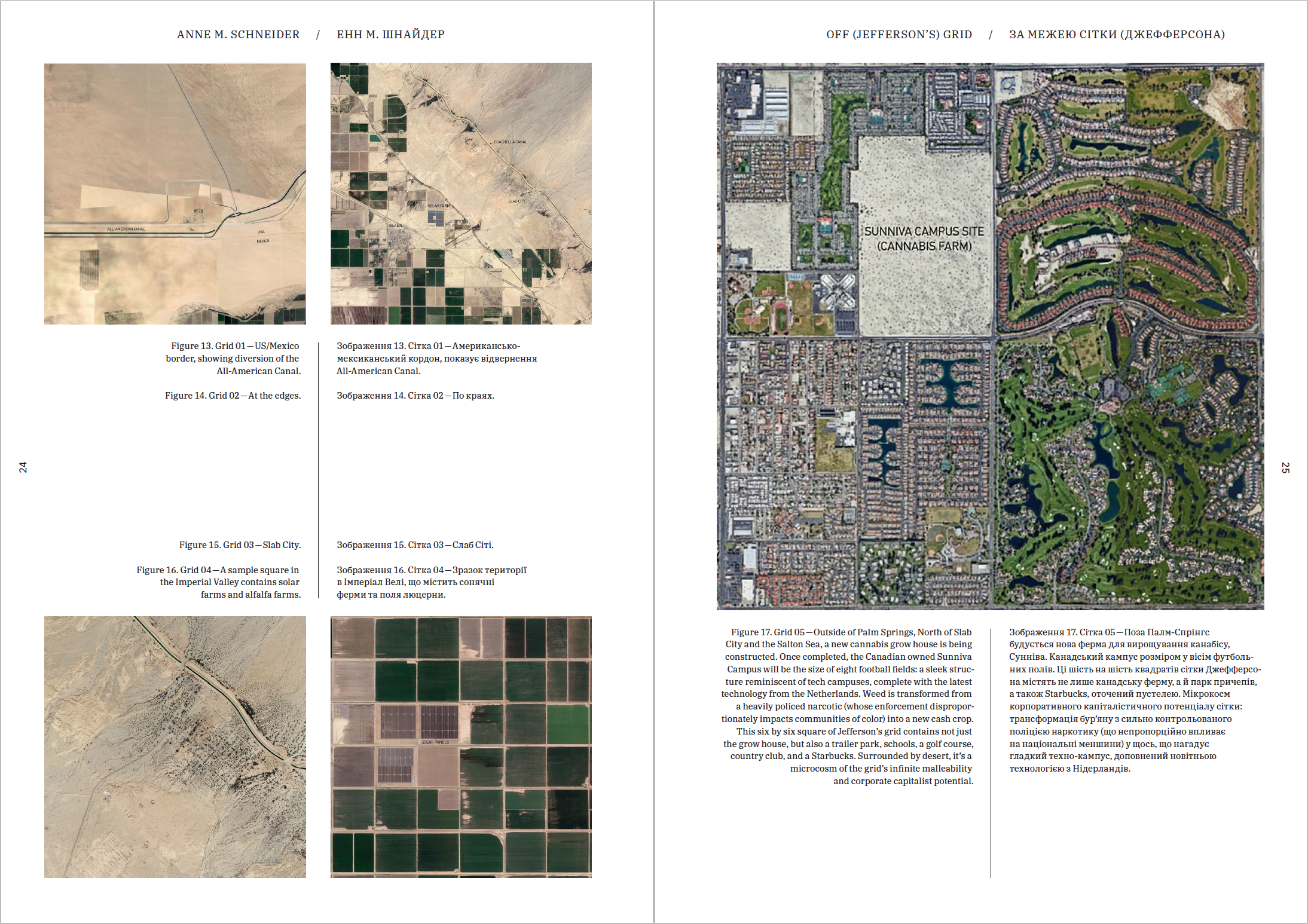

An aerial view of the Imperial Valley gives a mistaken impression of causality—farms created the Salton Sea, not the other way around [Fig. 7]. The largest body of water in California is an accident of in-the-grid-ambition, a form of liquid prometheanism (in the desert, you steal water not fire). Before irrigation, this stretch of desert was an undesirable afterthought known as the Salton Sink, named for its salt deposits. The survey grid of 1852 was hastily drawn,, off in places by as much as two miles (3.2 kilometers), and left to return to the sand.[1] Fifty years later, with the vast western expanses contracting and desirable land becoming scarce, the privately owned California Development Company dug the first canals from the Colorado River. Overnight, the desert bloomed: the Salton Sink was renamed the Imperial Valley: settlers came in droves, thousands of acres of agricultural land were cultivated, train tracks (the life-blood artery of 20th century commerce) were laid, and towns were built.

In 1905 the canals that created the Imperial Valley

almost destroyed it. Hastily dug and poorly managed, the canals filled with

silt. After heavy rains, they burst their banks and hemorrhaged the Colorado

River into the Salton Sink, 233’ below sea level. Eye-witness accounts read

like an Old Testament plague: a wall of water ten miles wide washed away

everything in its path; snakes fled the flood and infested the surrounding

settlements in a reversal of St. Patrick’s legend; thousands of fish, carried

by the waters, putrefied in the desert sun, a vicious olfactory assault that

could be smelled for miles.[2] For two years, the deluge menaced

cities, farms, and waterworks – both upstream and down. Only when its main Yuma

line was threatened did the Southern Pacific Railroad[3] intervene.

Tons of earth, rocks, and private money finally corralled the runaway river,

but the Salton Sea remained.

![]()

Despite the heat and an average rainfall of less than three inches (eight centimeters) a year, the lake remains, fed by a continual supply of agricultural runoff from American, Emirati, and Saudi-Arabian owned alfalfa farms. Festering in the sun and getting saltier and more toxic by the day, the few surviving fish stewing in agricultural run-off are nothing short of miraculous. Underlying it all is a deep, subterranean unease; the Sea is volcanically active, gurgling and hissing it sits atop the San Andreas Fault line, California’s ticking time bomb.

Despite the heat and an average rainfall of less than three inches (eight centimeters) a year, the lake remains, fed by a continual supply of agricultural runoff from American, Emirati, and Saudi-Arabian owned alfalfa farms. Festering in the sun and getting saltier and more toxic by the day, the few surviving fish stewing in agricultural run-off are nothing short of miraculous. Underlying it all is a deep, subterranean unease; the Sea is volcanically active, gurgling and hissing it sits atop the San Andreas Fault line, California’s ticking time bomb.

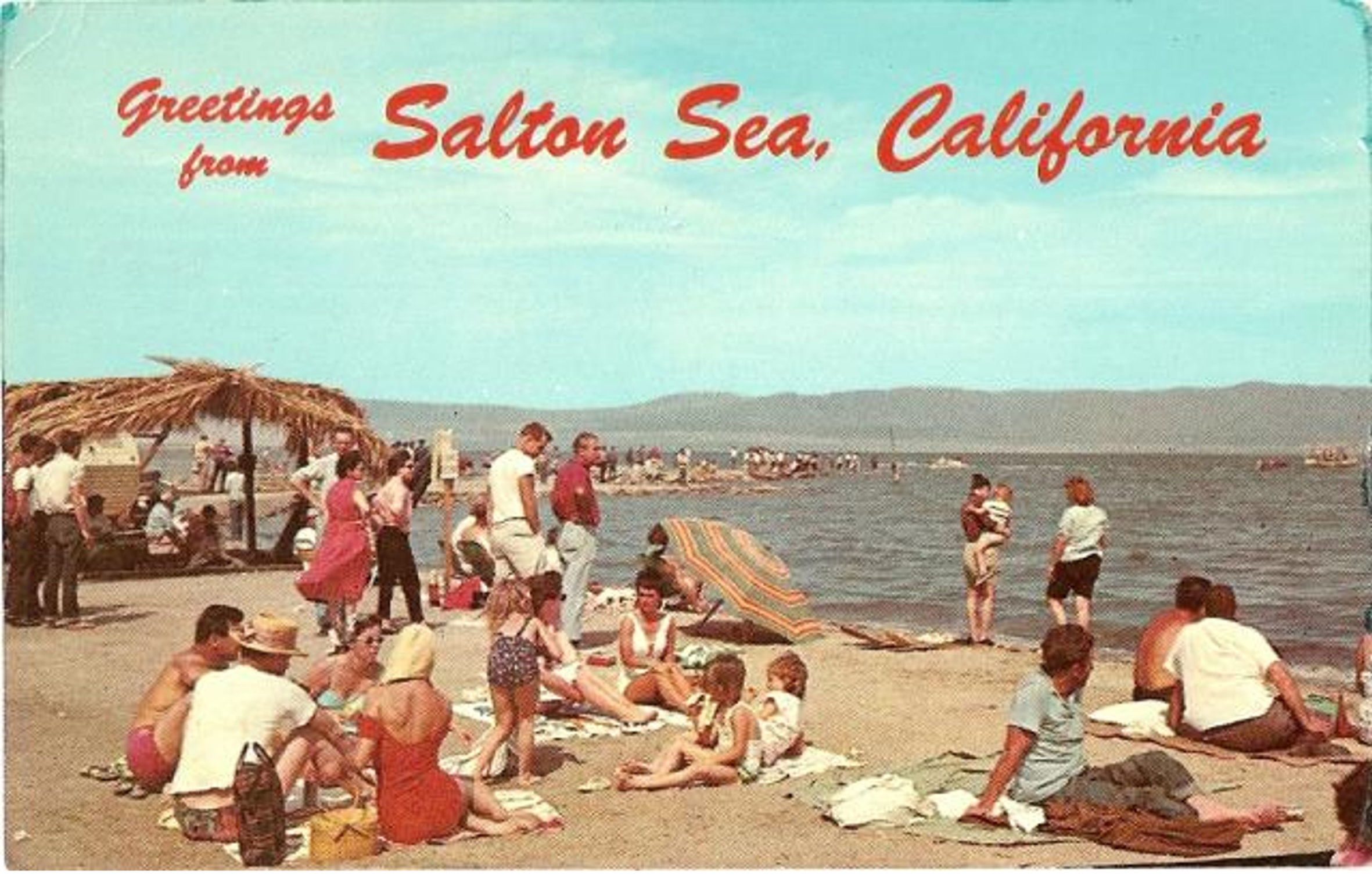

Water in the desert, the sea exerted an irresistible allure. As soon as it formed speculation began. Would-be fisherman and hoteliers stocked the water with fish (none survived) and imported sea lions (who disappeared without a trace). It was a short-lived naval base and a speedboat time-trial site. In the 1950s, leisure resorts, yacht clubs, and golf courses sprang up around the newly branded ‘California Riviera.’ Ringed by improbably named beaches—the North Shore, Mecca, Bombay Beach— it became, for a brief time, a desert mirage vacation destination for Los Angeles urbanites, attracting the likes of Frank Sinatra, the Beach Boys, the Marx Brothers, and Jerry Lewis.[4] Today, it’s a ghost town of thwarted ambitions, an eerie desolation of semi-abandoned motels and trailers.

40 miles long and 15 miles wide (65 kilometers by 24

kilometers), the Salton Sea is the Colorado River’s final resting place—the

river’s backwash. In the absence and disappearance of natural wetlands like the

Gulf of California (the river’s natural termination point) it has become an

unlikely yet vital ecosystem. The Sea, which resisted every human attempt at

cultivation, an environment so extreme that any life seems improbable, has

become a crucial stopover for migratory birds and home to one of the most

diverse avian populations in the continental US.[5]

[1] Hailey, Charlie, and Donovan Wylie. Slab City Dispatches from the Last Free Place. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018.

[2] Lafflin, Pat. Salton Sea: California's Overlooked Treasure, 30. Indio, CA: Coachella Valley Historical Society, 1999.

[3] In the fledgling state of California, the Southern Pacific Railroad was a titan of industry that wielded power and funds that rivaled any official body.

[1] Hailey, Charlie, and Donovan Wylie. Slab City Dispatches from the Last Free Place. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018.

[2] Lafflin, Pat. Salton Sea: California's Overlooked Treasure, 30. Indio, CA: Coachella Valley Historical Society, 1999.

[3] In the fledgling state of California, the Southern Pacific Railroad was a titan of industry that wielded power and funds that rivaled any official body.

Born of obsessive productivity and shameless

speculation, all the ingredients of the grid gone horribly awry, the Salton Sea

is an extra-large accident that refuses to evaporate. A glitch in the matrix (neither wholly natural nor wholly manmade) the

sea resists productivity and refuses definition. The lowest point in the Mojave

Desert, it remains a collection basin of detritus, water, and people.

[4] IBID, p. 41.

[5] Borunda, Alejandra. “The West Coast's Biggest Bird Oasis Is Dying. Will It Be Saved?” California's Salton Sea, a bird oasis, is dying. Will it be saved?, December 28, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/12/salton-sea-drying-up-bird-migration-health/.

[4] IBID, p. 41.

[5] Borunda, Alejandra. “The West Coast's Biggest Bird Oasis Is Dying. Will It Be Saved?” California's Salton Sea, a bird oasis, is dying. Will it be saved?, December 28, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/12/salton-sea-drying-up-bird-migration-health/.

SALVATION MOUNTAIN

15 minutes away by car, out of the scrubby baldness of the desert rises a half-slumped mirage, a cartoonist’s idea of an LSD trip—Salvation Mountain. Driven by messianic visions, artist-outsider Leonard Knight built out of the desert: adobe, straw, driftwood, and 500,000 gallons of latex paint applied directly to the canvas of the desert. Began in 1984—and rebuilt after the first version collapsed—Salvation Mountain is covered in technicolor patterns and ecstatic verse, some biblical, some original. “Jesus I’m a sinner, please come upon my body and into my heart,” Knight pleads; “God is Love” he declares in three-meter high letters. It’s the St. Peters of the Mojave, a roadside curio so far from the nearest road that it’s not a pit stop but a pilgrimage, a mecca for instagram influencers, road trippers, and a biographic blip for off-grid hero Chris McCandles.

Slab City

A two-minute drive down a soft dirt road with no Google street view is Slab City. 640 square acres of homestead land that nobody wanted– it is home to the homeless. Wealthy retirees, aged hippies, army veterans, Christian fundamentalists, burners, and drop-outs park their mobile homes on concrete slabs, all that remains of the US Marine Corp’s Camp Dunlap. General Patton drilled there and the Enola Gay flew practice runs before becoming the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.![]()

Officially, Slab City doesn’t exist. Like its resident “Slabbers,” it has fallen through the cracks. There is no water, no mail, no electricity, no garbage collection, no municipal services of any kind. There are also no laws, no taxes, and no foreclosures. Slabbers call it “the last free place.”

Jefferson spliced this legal loophole right into the DNA of the 1785 Land Ordinance, the biggest grid in the world. Slab City is sited on section 36, the township parcel designated for public education. Surveyed but never settled, Slab City is one square mile of desert intended for a school that was never built, owned by a state that can’t manage it, and patrolled by a sheriff’s department that is understaffed and has better things to do. Federal, state, and local authorities all turn a blind eye to one of the longest-lived squats in American history.

![]()

A two-minute drive down a soft dirt road with no Google street view is Slab City. 640 square acres of homestead land that nobody wanted– it is home to the homeless. Wealthy retirees, aged hippies, army veterans, Christian fundamentalists, burners, and drop-outs park their mobile homes on concrete slabs, all that remains of the US Marine Corp’s Camp Dunlap. General Patton drilled there and the Enola Gay flew practice runs before becoming the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Officially, Slab City doesn’t exist. Like its resident “Slabbers,” it has fallen through the cracks. There is no water, no mail, no electricity, no garbage collection, no municipal services of any kind. There are also no laws, no taxes, and no foreclosures. Slabbers call it “the last free place.”

Jefferson spliced this legal loophole right into the DNA of the 1785 Land Ordinance, the biggest grid in the world. Slab City is sited on section 36, the township parcel designated for public education. Surveyed but never settled, Slab City is one square mile of desert intended for a school that was never built, owned by a state that can’t manage it, and patrolled by a sheriff’s department that is understaffed and has better things to do. Federal, state, and local authorities all turn a blind eye to one of the longest-lived squats in American history.

Slab City has existed for almost 70 years, part of the same post-war euphoria that saw the Salton Sea briefly transformed into an oasis vacation destination, and has everything you would expect from a town: a church, a library, a (pet) cemetery, a main street, and “good” and “bad” parts of town.

Its population fluctuates—from less than one hundred during the sweltering summer months to over a thousand at its peak. In July the whole place has an air of abandonment: everyone who could leave has already left. In winter, the population swells with snowbirds, their $300,000 shiny Coachmen and Ramblers parked in orderly rows. Once advertised in Trailer Life magazine, targeted towards budget-conscious retirees, as a free place to park[1] Slab City may be the last free place to park your RV anywhere, and maybe the last free place, period.

An unintentional community held together by a legal loophole and neglect, there’s no cohering ideology or faith or belief. Like the Salton Sea, Slab City is an enduring accident, an aberration, created by the grid itself. Threaded through the extra-large organizational framework of the nation—the survey grid that divided the west before we’d even seen it—are places and people that, to this day, resist cultivation, organization, and the grid’s imperative of productivity.

[1] Sanjiv Bhattacharya, “Land of the Free,” Guardian, March 22, 2003.

PUBLICATIONS: